Crack and Creation

(Translated by Claude AI)

Abstract

Culture is a creative process because the real presents itself as a web of relations in act. Truth is neither static possession nor arbitrary construction, but formative correlation between the one who thinks and that which is thought: the adequatio rei et intellectus is the form that such correlation assumes.

Every configuration of truth acts as ontological transformation: it reorganizes connections, modifies possibilities, redistributes constraints. Cultural history is traversed by rigidifications and dogmatisms: systems are constructed to make the world habitable, necessary maps that permit its usability and predictability.

But precisely at the point of maximum coherence emerges that which does not allow itself to be absorbed.

The crack is not a defect: it is the structure of the perichoretic triad. Possibility, Necessity and Reality never coincide perfectly, and this non-coincidence is an ontological condition. The creation of forms is necessary; the impossibility of closing them is constitutive.

Art—from the Doryphoros to the Laocoön, from Morandi to Cage—manifests this structure plastically: the fissure as distance, tension, open question.

1. Culture as formative correlation

Culture is not a repository of contents, but a process of configuration. Truth is not a static object, but a relation. There is no truth without the relationship between the one who thinks and that which is thought. The adequatio rei et intellectus—in the formulation of Thomas Aquinas (Summa Theologiae I, q. 16, a. 1), inherited from Avicenna (Liber de philosophia prima I, 8)—does not indicate a photograph of the object but the successful act of correlation. In Thomas the veritas reiprecedes knowledge (the thing is true in relation to the divine intellect); here only the formative correlation is assumed, without transcendent foundation. This correlation is not epistemological but ontological: it configures the way in which the triad Possibility–Necessity–Reality enters into perichoretic circulation. And since the world is not a set of isolated entities, but rather a web of relations continuously in act, every new configuration of this correlation does not remain confined to the cognitive sphere: it reorganizes connections, modifies operative possibilities, redistributes constraints. Truth, in this sense, is a process not only cognitive but concrete: a form that, by adequating, transforms.

If this is the case, philosophy is an art in the rigorous sense: not the art of free invention, but the art of adequate structure. An art that produces, knows and organizes the true. It does not substitute the world with a narrative; it attempts to give the correlation a form that holds.

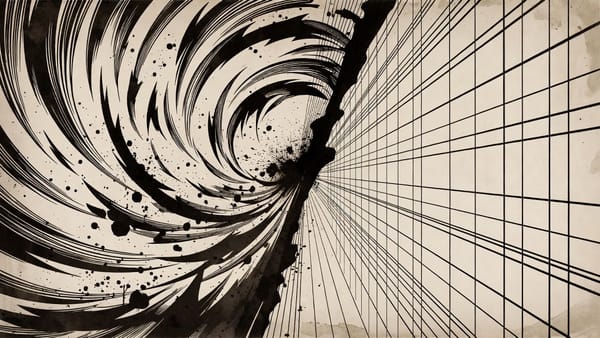

2. The system, the dogma and the residue

The history of philosophy is a sequence of attempts at stabilization. Plato separates the order of Ideas from the sensible to guarantee permanence; Aristotle organizes being into categories and causes; Kant delimits knowing by distinguishing phenomenon and noumenon; Hegel integrates contradiction into the movement of the concept. In each case the system arises as an attempt at adequation: a coherent form of the correlation between intellect and world.

This perspective does not coincide with the idea, often invoked today, of a generalized dissolution of forms. Culture is not a liquid flux that would render every stability impossible; on the contrary, it is traversed by rigidifications, dogmatisms, claims of absolute necessity. Systems are constructed to make the world habitable: always approximate maps that permit its usability and predictability. But the risk is twofold: on the one hand, forgetting that they are maps; on the other, claiming that they can be definitive. The dynamism inherent in the structure of the real and in the formative correlation prevents every closure: systems attempt to eliminate excess, neutralize the remainder, declare the question concluded.

And yet, precisely at the point of maximum coherence or maximum dogma, emerges that which does not allow itself to be absorbed. Platonic methexis remains an unstable bridge; the Aristotelian unmoved mover introduces a dimension that exceeds pure logic; the Kantian noumenon is necessary but untouchable; the Hegelian totality encounters a historical world that does not coincide with its formalization. The crack is not a secondary defect: it is the structural trace that adequation cannot close once and for all.

The crack is not an empirical residue that the form does not capture, nor a dialectical tension destined for Aufhebung. It is the very structure of the perichoretic triad: Possibility, Necessity and Reality never coincide perfectly, and this non-coincidence is not error but ontological condition. Every system stabilizes a configuration of the triad, but no configuration can annul the circulation among the three moments. The remainder that emerges—methexis, unmoved mover, noumenon—attests that formal closure reproduces the gap it claimed to eliminate.

Vitality reemerges creating cracks in concepts, in institutions, in images.

3. Classical perfection: the Doryphoros and the crack as distance

If one wishes to understand the crack in its most subtle form, one must look to the art of full classicism, where perfection seems to speak the language of measure.

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is the image of proportion as law: a body not empirical, but normative. Beauty does not arise from expressivity, but from the calculated relation among the parts. It is a perfection that does not ask for indulgence: it demands exactitude.

And precisely for this reason it produces distance. The Doryphoros does not coincide with any body actually given; it is the measure of the body, not the body. Perfection, here, does not pacify the world: it suspends it. Contemplating the ideal we are not confirmed in the existent; we are "torn" from its obviousness. The crack is not in the marble; it is between the work and life. It is the gap between what we are and what, for an instant, appears as the fully coherent form of the possible.

In this sense classical art does not eliminate the fissure: it institutes it as distance. The ideal does not console, because it shows that the real is an approximation; and yet it does not humiliate, because it indicates that the real is also openness, not only given. Formal perfection reveals a structural truth: the existent does not coincide with the measure that makes it thinkable.

4. The emergence of the crack: the Laocoön as visible tension

With Hellenism the fissure no longer remains only distance between ideal and real; it becomes internal tension within the form.

The Laocoön offers an illustrative case of the crack as internal tension within the form. Winckelmann still read in it "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur"; Lessing (Laocoön, 1766) noted its expressive limits compared to poetry. Here the group is of interest as a plastic manifestation of an ontological structure: the body not as equilibrium, but as field of forces—torsion, resistance, constraint. The form holds because it brings into figure the friction between possibility and necessity. This does not prove that all Hellenistic art operates thus, but it shows a configuration of the fissure: the crack no longer as distance (Doryphoros) but as internal tension within the act.

The crack has become plastic. It is no longer only in the spectator who measures the distance from the ideal; it is in the matter itself, which shows how unity is a precarious result. Beauty does not cancel the wound; it structures it. And by structuring it, it makes it knowable, that is adequate, without thereby domesticating it. Here too the adequatio is not copy: it is form adequate to a truth of the real, namely that order is never pure, but always traversed.

The passage from the Doryphoros to the Laocoön is not decadence, but explicitation. The tension that in the classical was silent becomes visible. The crack emerges.

5. Remaining in the fissure

Modernity makes explicit what tradition had already encountered: the impossibility of closing being in a definitive form. Nietzsche affirms that only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence justifiable[1]: form is that which makes the excess of the real habitable. Heidegger, analyzing technology as Gestell, shows the contrary risk: reducing the world to available resource, canceling the residue, treating every friction as error[2]. But canceling the residue means canceling precisely that which makes the real greater than its management.

The crack finds different configurations in twentieth-century art. The choice of the following four cases is only one among many possible—it mainly reflects the author's tastes, who is not an art expert, especially of contemporary art—and has no claim to taxonomy: it serves solely to show how the ontological structure of non-coincidence can manifest itself plastically.

Giorgio Morandi, in his mature still lifes, arranges bottles and objects in configurations where each element exists only through the distance that separates it from the others. They never touch; yet they could not exist separately. The gap between the objects is not void but ontological condition: that which logically should be absence founds the presence of each. The crack is the constitutive distance.

John Cage, in 4'33'' (1952), composes a piece in which no sound is intentionally produced. The work exists only as distance between compositional intention (the score that prescribes non-playing) and the unpredictable acoustic event. Every performance is ontologically different. The work interrogates its own foundation—what is music?—without resolving it. The crack is the question that cannot be closed.

Mark Rothko, in his large chromatic fields, dissolves the boundary between color planes. There are no forms to recognize, there is no narration. The work exists uniquely in the event of encounter: what happens between the spectator and the surface depends on a tension not controllable, not repeatable. Rothko himself declared that his paintings "live" only at a precise distance—too close or too far, they collapse. The crack is the tension that holds the work in being without stabilizing it.

Jan Fabre, in works like Tivoli (2003–2013)—walls entirely covered with beetle elytra—or in drawings with the artist's blood, uses materials that carry death with them (the dead insect, the extracted blood). Beauty—the blue iridescence of the beetle shells, the precision of the drawing—emerges precisely from the matter that attests to the end. There is no synthesis: splendor and decomposition coexist without canceling each other. The crack is the impossible coexistence that becomes the condition of the work.

Four configurations: constitutive distance, open question, irresolvable tension, paradoxical coexistence. In each case the crack is not defect but structure: the work manifests that possibility, necessity and reality do not coincide, and that this non-coincidence is the condition of being.

If truth is formative correlation, it cannot be possessed once and for all. Every truth is a configuration that succeeds and that, precisely because it succeeds, acts: it transforms the world by reorganizing the web of relations in which entities stand. The crack, as structural non-coincidence among the three moments, cannot be eliminated: every attempt at closure necessarily reproduces the gap it claimed to annul. Philosophy, as art of structure, does not close the world; it prevents the world from being closed.

Notes

[1] F. Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödie, §5, in Sämtliche Werke. Kritische Studienausgabe, ed. G. Colli and M. Montinari, vol. 1, Berlin-New York, de Gruyter, 1988, p. 47.

[2] M. Heidegger, "Die Frage nach der Technik", in Vorträge und Aufsätge, Pfullingen, Neske, 1954; Eng. trans. "The Question Concerning Technology", in Basic Writings, ed. D. F. Krell, New York, Harper & Row, 1977, pp. 283–317.

Essential bibliography

Avicenna, Liber de philosophia prima (Metaphysics), ed. S. Van Riet, Louvain-Leiden, Peeters-Brill, 1977–1983.

M. Heidegger, Vorträge und Aufsätze, Pfullingen, Neske, 1954; Eng. trans. Basic Writings, ed. D. F. Krell, New York, Harper & Row, 1977.

G. E. Lessing, Laokoon oder über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie (1766); Eng. trans. Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, trans. E. A. McCormick, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

F. Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödie, in Sämtliche Werke. Kritische Studienausgabe, ed. G. Colli and M. Montinari, vol. 1, Berlin-New York, de Gruyter, 1988.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I, q. 16.