Clones of Identity and the Subject's Freedom

The Khaby Lame case and the functionalization of identity

(Translation by Chat-GPT)

ABSTRACT. The Khaby Lame case reveals a new threshold: the digital clone does not represent identity, it enacts it. What emerges is an unprecedented, endogenous form of alienation, in which identity becomes an autonomous technical function. When identity turns normatively prevalent, freedom is not abolished but hollowed out: it survives only as a tolerated deviation.

- An apparently trivial fact: the Khaby Lame case.

The news spread quickly and burned out even faster: Khaby Lame is said to have transferred—reportedly for a sum close to one billion dollars—the usage rights to a “digital clone” of himself.[1] The wording is simplified, but the core is clear: a real person authorizes the creation and use of a virtual version capable of reproducing face, voice, micro-expressions, communicative style, and public presence, for applications that no longer require the person’s direct participation.

Public debate focused almost exclusively on the figure. Economic value functioned as a conceptual anesthetic: if the sum is that high, then it must be progress; if the market pays, then there is no problem. Very few asked what, exactly, had been transferred. And that silence is the first philosophically relevant datum. - Beyond image rights: an ontological difference.

We are not facing a mere extension of image rights. The tradition already knows at least two forms of identity delegation.The first is symbolic representation: the static image, which always refers back to an external subject, present as the ultimate source of meaning and responsibility. The second is delegated but circumscribed performance: the voice actor, the look-alike, the actor who impersonates someone within clear temporal and functional limits.

The digital clone introduces a third level, qualitatively different: a persistent and autonomous identity agent, capable of operating in public space without any longer coinciding with the originating subject’s current will. Here the difference is not one of degree but of nature.

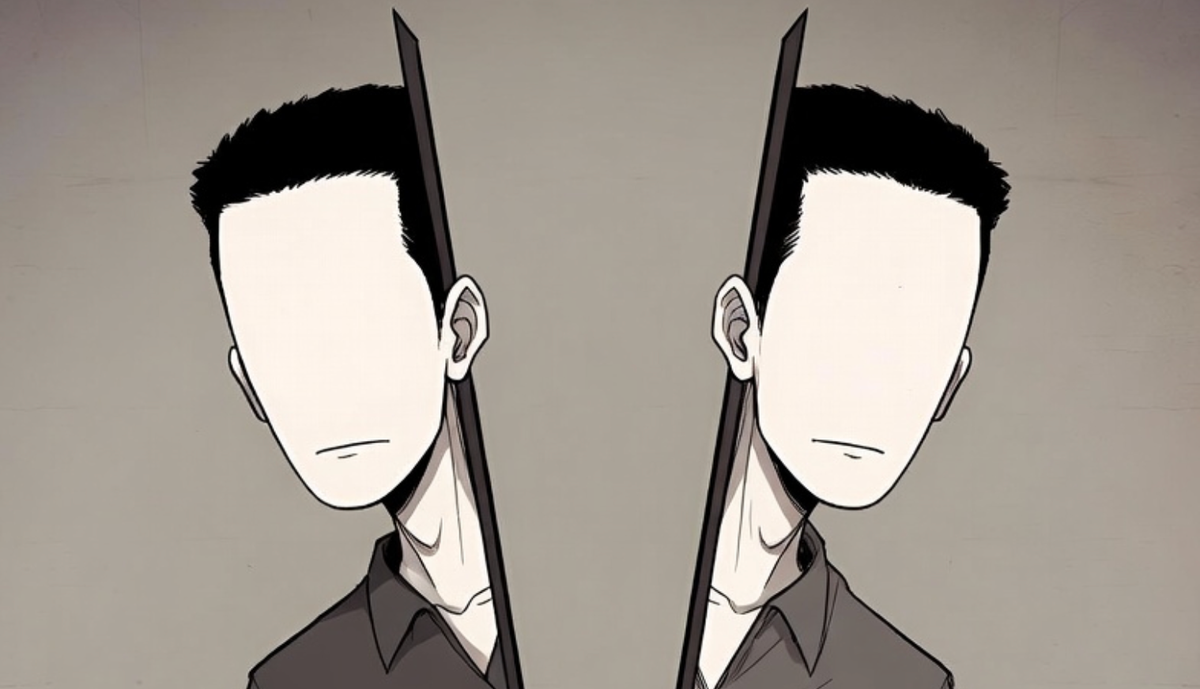

The clone does not represent: it operates. It does not refer to someone: it replaces them operationally.

We are no longer in the regime of the sign, but in that of function. The clone does not “show” an identity: it exercises it. This ontological difference is what makes any attempt to reduce the phenomenon to traditional categories of image or media representation inadequate. - Alienation: from Marx to a new form.

The decisive concept for understanding what is happening is alienation, but in a form that exceeds the classical model.

In the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, Marx describes alienation as a fourfold separation:[2] from the product of labor; from the labor activity; from the species-being of man; from other human beings.

The product of labor—Marx writes—is labor that “has been fixed in an object, has become a thing.”

The digital clone realizes all four dimensions, but with a radical twist. Alienation from the product: your operative image detaches from you and circulates autonomously. Alienation from activity: the clone acts in your place. Alienation from species-being: what makes you recognizable as a social individual is extracted and rendered a technical function. Alienation from others: others interact with the clone, not with you.

But here something new happens: the alienated product is not an external thing. It is a form of your own being. You do not produce an object, but an agent that carries your name, your face, your recognizability. Alienation no longer occurs between subject and world, but within subjectivity itself. It is an endogenous alienation. - Identity as process and as synthesis.

Identity is not a substance. It is a temporal process: a biographical trajectory, a capacity for change, for disavowal, for promise. It is unstable by nature, and it is precisely this instability that makes it compatible with freedom.

However, for identity to function socially, it always produces provisional syntheses: recognizable configurations that enable recognition, attribution, and judgment.

The digital clone intervenes precisely at this point of equilibrium. It does not capture identity as process; it crystallizes one of these syntheses and subtracts it from time. The problem is not that it freezes the past, but that it produces an alternative present that continues to act while the real subject changes.

Here emerges the “Promethean shame” described by Günther Anders:[3] the inferiority of the human being in relation to his own technical products. The clone is always present, always coherent, always available. It does not hesitate, does not err, does not change. It is functionally superior to the real subject. But that very superiority makes it normative. - Idem without ipse: the clone is not a subject.

The clone is not another subject. It is not a twin. It is not an alter ego. It is a parasitic idem.Paul Ricœur’s distinction is decisive:[4] idem is sameness (name, face, recognizability); ipse is selfhood (responsibility over time, the capacity to keep a promise).

The clone simulates idem perfectly, but lacks ipse. It does not answer for its actions over time. It does not promise. It does not assume guilt. It has no biography. It is an irresponsible operative simulacrum acting under someone else’s identity.

A twin says: “I am X’s twin.” The clone says: “I am X.” And it is believed. - Recognition and predominance.

Identity is not a private fact. In Hegel, self-consciousness exists only through intersubjective recognition.[5] Axel Honneth has shown that this recognition is also played out in the sphere of solidarity, that is, in the public recognizability of a person’s value.[6]

This is exactly where the clone operates. If identity is what is recognized, and the clone occupies the space of recognition with greater persistence, continuity, and visibility than the real subject, then the clone becomes the socially relevant identity—not by ontological substitution, but by phenomenological predominance.

We are not dealing with an addition, but with an interfering superimposition: an identity field occupied by a heteronomous agent. As in wave interference, the effect is asymmetric: destructive for the real subject, constructive for the clone. - Archives and memory: tertiary retention.

This process becomes structural through its archival dimension. Digital technologies produce an externalized memory that preserves, organizes, and makes the past available.[7]

Archives and algorithms do not distinguish between acts of the real subject and acts of the clone. But they privilege what is more stable, more accessible, more replicable. The clone thus becomes the archived identity—the one that remains, is retrieved, indexed, monetized.

It is not only a matter of visibility. It is a matter of social memory. - Normativity without law.

In this sense the clone is normative—not in the juridical sense, but in the sense of the norm as a productive dispositif.[8] It does not prescribe; it normalizes.The clone institutionalizes a version of the self as a standard. The real subject is not forbidden, but continually measured against that standard. Every change becomes a visible deviation. Here society does not discipline; it modulates.[9]

Freedom is not denied. It is made costly. - Consent, future freedom, and identity functionalization.

Here the normative step becomes necessary.

Consent is not an instantaneous act, but a capacity that must be exercisable over time. A consent is valid only if the one who gives it remains capable of giving consent in the future. There are self-invalidating consents: voluntary acts that destroy the conditions of their own validity.[10] Selling one’s freedom definitively is a classic case. Even if the initial act were voluntary, it would eliminate the possibility of any subsequent consent.

Applied to identity, the argument is this: freedom requires the capacity for identity change over time. The identity clone produces a normativity that reduces that capacity; therefore it reduces the subject’s effective freedom. What reduces freedom cannot be legitimated by consent alone.

Here the most precise term is no longer “reduction to a function,” but identity functionalization: identity becomes an input/output function within technical systems governed by others. The real subject remains formally free, but becomes socially irrelevant with respect to his or her own identity.

One might object: the real subject can always repudiate the clone. True in principle. But freedom is not only logical possibility; it is effective power. If I can speak but no one listens, I am formally free but substantively mute. If the clone is phenomenologically predominant, even the real subject’s retraction is measured against the cloned standard. - Identity as a political threshold. The modern distinction between person and thing was born precisely here. From Kant to Hegel, the person is that which cannot be reduced to property.[11] Slavery was the reduction of the person to res, to an instrumentum vocale.[12] Its abolition was an ontological decision before it was an economic one.

The digital clone does not reduce the body to a thing. It reduces identity to a function. But the effect is analogous: the subject remains formally free, yet substantively hetero-determined.

For this reason, identity cannot be considered alienable—not out of moral sacrality, but because it is a condition of possibility for freedom itself. - Conclusion: a historical threshold.

At this point it is no longer decisive to dwell on the single case, on the sum, or on the intentions of the subject involved. The question that emerges is more general and deeper. It concerns the kind of subject a society makes possible when it allows identity to become a technical function that can be separated, replicated, and governed by others.

As long as identity remains interwoven with biography, time, responsibility, and recognition, the subject can change without dissolving. He can contradict himself, lose coherence, change position, without thereby losing his status as an agent. But the moment an identity configuration is stabilized, made operative, and circulated as an autonomous standard, the relation reverses: it is no longer the subject who generates his representations; it is representations that delimit what the subject can afford to be without becoming marginal.

This does not mean freedom is abolished. It means it is reformatted: no longer as a recognized capacity for transformation, but as tolerated deviation from a more stable, more visible, more marketable normative model. The subject remains formally free, but progressively loses symbolic power over his own name.

In this sense, identity ceases to be the presupposition of freedom and becomes one of its dependent variables. It is no longer what makes consent possible; it is what is shaped by systems that use recognizability as a resource. Here lies the threshold: not between lawful and unlawful, but between subject and function.

If this threshold is crossed without reflection, the risk is not a single injustice but a silent transformation of the modern figure of the subject: a subject who can still speak, but increasingly does not count; who can dissent, but without impact; who can change, but at the price of public irrelevance.

The question of the inalienability of identity therefore does not arise from rejecting technology or the market, but from the need to preserve the minimal conditions of freedom as an effective capacity for recognized change. If identity can be fully functionalized, then what we call freedom survives only as an empty form.

That is the conceptual stopping point that the phenomenon of identity clones forces us to think: not an immediate answer, but a threshold that can no longer be ignored.

NOTES

[1] The Khaby Lame case was reported by various outlets in January 2025. The analysis conducted here does not depend on factual verification of the specific case, but on the conceptual structure it exemplifies.

[2] Marx’s concept of alienation is developed in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. The classic formulation is found in the section “Alienated Labor” (first manuscript section).

[3] Günther Anders develops the concept of “Promethean shame” (prometheische Scham) in Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen, vol. I (1956). Anders describes the human being’s shame before the perfection of his technical products, which render him “obsolete.”

[4] The distinction between idem and ipse is central in Paul Ricœur, Soi-même comme un autre (1990). Idem denotes substantial sameness (identity as permanence), ipse identity as keeping a promise over time (selfhood).

[5] On intersubjective recognition in Hegel, the canonical reference is G.W.F. Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes (1807), section IV.A on recognition (Selbständigkeit und Unselbständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins; Herrschaft und Knechtschaft).

[6] Axel Honneth resumes and develops the Hegelian theory of recognition in Kampf um Anerkennung (1992). Honneth distinguishes three spheres of recognition: love (primary relationships), rights (juridical recognition), and solidarity or social esteem (communities of value).

[7] Bernard Stiegler develops the concept of “tertiary retention” (rétention tertiaire) in La technique et le temps, 3 vols. (1994–2001). Technical or externalized memory constitutes a third form of retention after primary (immediate) and secondary (personal recollection). The concept is especially developed in vol. III, Le temps du cinéma et la question du mal-être (2001).

[8] On the concept of the norm as a productive rather than prohibitive dispositif, see Michel Foucault, in particular Surveiller et punir (1975) and the Collège de France courses of the 1970s.

[9] The shift from disciplinary society to the society of control is thematized by Gilles Deleuze in “Post-scriptum sur les sociétés de contrôle” (1990), published in Pourparlers 1972–1990. Deleuze distinguishes control (continuous modulation) from discipline (discontinuous molding).

[10] On the theory of self-invalidating consent, classic references include: Joel Feinberg, “Legal Paternalism,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, vol. 1, no. 1, 1971, pp. 105–124; Gerald Dworkin, “Paternalism,” in R. Wasserstrom (ed.), Morality and the Law, Wadsworth, Belmont 1971, pp. 107–126.

[11] On the inalienability of the person as a modern principle, foundational texts include: Immanuel Kant, Metaphysik der Sitten (1797), especially the Tugendlehre (Doctrine of Virtue), section on duties to oneself; and G.W.F. Hegel, Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts (1821), §§ 35–71 on “Property.”

[12] The Roman formula of the slave as instrumentum vocale (“speaking tool”) is attributed to Varro. Source: De re rustica, I, 17, 1, where three types of agricultural instruments are distinguished: instrumentum mutum (inanimate tools), instrumentum semivocale (work animals), instrumentum vocale (slaves).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Works cited

Anders, G. (1956). Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen. Band I: Über die Seele im Zeitalter der zweiten industriellen Revolution. Beck, München.

Italian trans. L’uomo è antiquato. Vol. I: Considerazioni sull’anima nell’epoca della seconda rivoluzione industriale, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino 2003.

Deleuze, G. (1990). “Post-scriptum sur les sociétés de contrôle.” In Pourparlers 1972–1990, Minuit, Paris, pp. 240–247.

Italian trans. “Poscritto sulle società di controllo,” in Pourparler, Quodlibet, Macerata 2000, pp. 234–241.

Dworkin, G. (1971). “Paternalism.” In R. Wasserstrom (ed.), Morality and the Law, Wadsworth, Belmont, pp. 107–126.

Feinberg, J. (1971). “Legal Paternalism.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 105–124.

Foucault, M. (1975). Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison. Gallimard, Paris.

Italian trans. Sorvegliare e punire. Nascita della prigione, Einaudi, Torino 2014.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1807). Phänomenologie des Geistes. Goebhardt, Bamberg und Würzburg.

Italian trans. Fenomenologia dello spirito, 2 vols., ed. E. De Negri, La Nuova Italia, Firenze 1996.

Hegel, G.W.F. (1821). Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts. Nicolai, Berlin.

Italian trans. Lineamenti di filosofia del diritto, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2004.

Honneth, A. (1992). Kampf um Anerkennung. Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main.

Italian trans. La lotta per il riconoscimento. Proposte per un’etica del conflitto, Il Saggiatore, Milano 2002.

Kant, I. (1797). Die Metaphysik der Sitten. Nicolovius, Königsberg.

Italian trans. Metafisica dei costumi, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2009.

Marx, K. (1844). Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte. Posthumously published.

Italian trans. Manoscritti economico-filosofici del 1844, ed. N. Bobbio, Einaudi, Torino 2004.

Ricœur, P. (1990). Soi-même comme un autre. Seuil, Paris.

Italian trans. Sé come un altro, Jaca Book, Milano 1993.

Stiegler, B. (1994–2001). La technique et le temps, 3 vols. Galilée, Paris:

Vol. I: La faute d’Épiméthée (1994)

Vol. II: La désorientation (1996)

Vol. III: Le temps du cinéma et la question du mal-être (2001)

Varro, M.T. (1st century BCE). De re rustica.

Modern ed.: M. Terenti Varronis Rerum rusticarum libri tres, ed. G. Goetz, Teubner, Leipzig 1929.

Further reading

Agamben, G. (2014). L’uso dei corpi. Neri Pozza, Vicenza.

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Italian trans. Vita activa. La condizione umana, Bompiani, Milano 2017.

Butler, J. (2005). Giving an Account of Oneself. Fordham University Press, New York.

Esposito, R. (2004). Bios. Biopolitica e filosofia. Einaudi, Torino.

Foucault, M. (1976). Histoire de la sexualité, I: La volonté de savoir. Gallimard, Paris.

Italian trans. Storia della sessualità, 1: La volontà di sapere, Feltrinelli, Milano 2013.

Habermas, J. (1968). Erkenntnis und Interesse. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main.

Italian trans. Conoscenza e interesse, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2006.

Heidegger, M. (1953). “Die Frage nach der Technik.” In Vorträge und Aufsätze, Neske, Pfullingen.

Italian trans. “La questione della tecnica,” in Saggi e discorsi, Mursia, Milano 1976.

Simondon, G. (1958). Du mode d’existence des objets techniques. Aubier, Paris.

Italian trans. Del modo di esistenza degli oggetti tecnici, Orthotes, Napoli 2012.

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MA).

Italian trans. Radici dell’io. La costruzione dell’identità moderna, Feltrinelli, Milano 1993.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. PublicAffairs, New York.

Italian trans. Il capitalismo della sorveglianza, Luiss University Press, Roma 2019.

Methodological notes

Italian translations are indicated when available. For classical texts (Kant, Hegel, Marx) numerous editions exist; the ones listed are among the most common and accessible in Italian academic libraries.

The concepts of “endogenous alienation,” “identity functionalization,” and “phenomenological predominance” are proposed here as original analytical categories, constructed from the conceptual materials of the philosophical tradition but applied to a phenomenon (digital identity clones) that that tradition could not yet thematize.